Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes associated with government debt, leading them to save rather than increase spending, neutralizing fiscal policy effects. Barro-Ricardo equivalence refines this theory by emphasizing that individuals base their savings decisions on the entire intertemporal budget constraint of the government, reinforcing the idea that deficit financing does not affect aggregate demand. Both concepts challenge traditional Keynesian views by asserting that government borrowing does not stimulate consumption, highlighting the importance of expectations and rational behavior in economic policy analysis.

Table of Comparison

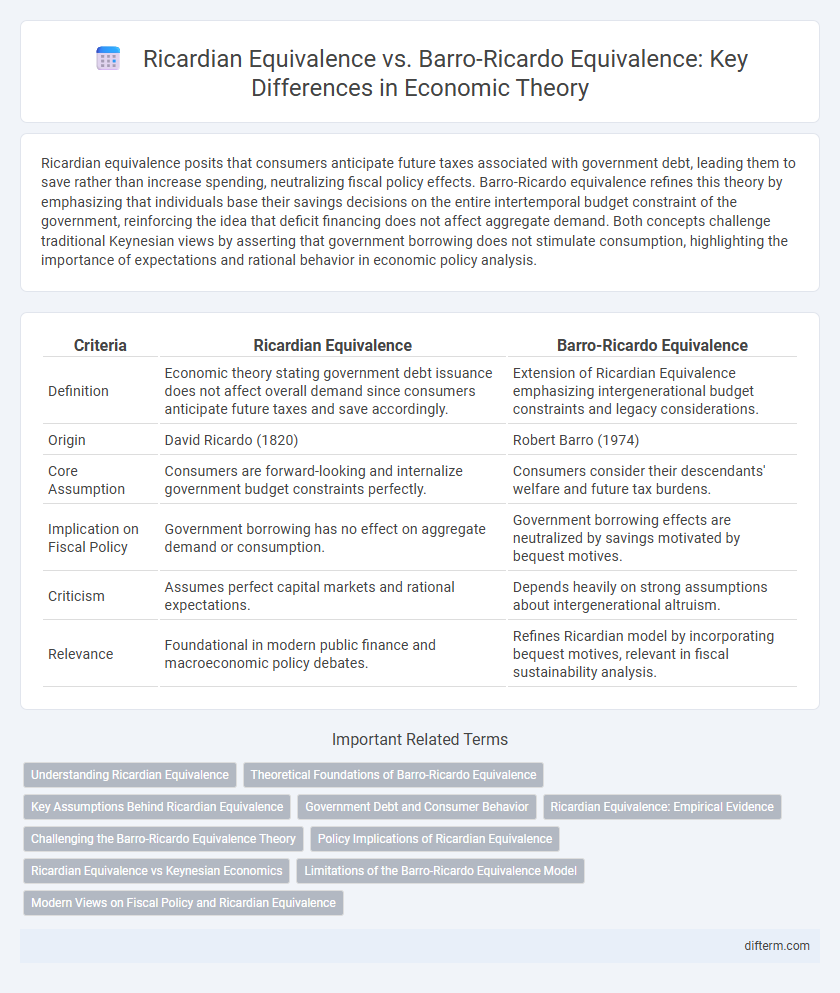

| Criteria | Ricardian Equivalence | Barro-Ricardo Equivalence |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Economic theory stating government debt issuance does not affect overall demand since consumers anticipate future taxes and save accordingly. | Extension of Ricardian Equivalence emphasizing intergenerational budget constraints and legacy considerations. |

| Origin | David Ricardo (1820) | Robert Barro (1974) |

| Core Assumption | Consumers are forward-looking and internalize government budget constraints perfectly. | Consumers consider their descendants' welfare and future tax burdens. |

| Implication on Fiscal Policy | Government borrowing has no effect on aggregate demand or consumption. | Government borrowing effects are neutralized by savings motivated by bequest motives. |

| Criticism | Assumes perfect capital markets and rational expectations. | Depends heavily on strong assumptions about intergenerational altruism. |

| Relevance | Foundational in modern public finance and macroeconomic policy debates. | Refines Ricardian model by incorporating bequest motives, relevant in fiscal sustainability analysis. |

Understanding Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian Equivalence posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes needed to repay debt, leading them to save rather than spend. This theory assumes forward-looking behavior and perfect capital markets, implying that fiscal deficits are neutral in their impact on the economy. Barro-Ricardo Equivalence extends this framework by emphasizing intergenerational altruism, suggesting that individuals consider the tax burden on their descendants, reinforcing the notion that public debt has no effect on aggregate consumption.

Theoretical Foundations of Barro-Ricardo Equivalence

Barro-Ricardo equivalence builds on Ricardo's original hypothesis by incorporating rational expectations and intergenerational altruism, asserting that government debt issuance does not affect overall demand since individuals anticipate future taxes. The theory presumes that households internalize the government's budget constraint, adjusting their saving behavior to offset fiscal policy changes. This framework highlights the role of forward-looking agents in maintaining macroeconomic neutrality despite public borrowing.

Key Assumptions Behind Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian equivalence rests on the key assumption that individuals are forward-looking and internalize government budget constraints, anticipating future tax liabilities caused by current debt. Households are assumed to have perfect access to capital markets, enabling them to smooth consumption over time despite government borrowing. The theory also presumes no distortionary taxes or liquidity constraints, allowing consumers to fully offset government deficits with private saving.

Government Debt and Consumer Behavior

Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes due to government debt issuance and thus increase savings to offset expected tax burdens, resulting in unchanged overall demand. Barro-Ricardo equivalence extends this theory by emphasizing that rational consumers fully internalize government budget constraints, making debt financing effectively neutral in influencing aggregate consumption. Empirical studies reveal variations in consumer behavior depending on liquidity constraints and intergenerational considerations, challenging the complete validity of both models in real-world fiscal policy analysis.

Ricardian Equivalence: Empirical Evidence

Empirical evidence on Ricardian equivalence reveals mixed results, with some studies supporting the notion that consumers foresee future tax liabilities and adjust their savings accordingly, while others find partial or negligible effects. Research often highlights that factors such as liquidity constraints, myopia, and imperfect capital markets limit the full realization of Ricardian equivalence in practice. Overall, empirical investigations suggest that the theoretical prediction of complete offsetting behavior between government borrowing and private saving is rarely observed in real-world economies.

Challenging the Barro-Ricardo Equivalence Theory

Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes linked to government debt, leading them to save rather than increase spending, effectively neutralizing fiscal stimulus. Barro-Ricardo equivalence refines this by emphasizing intergenerational altruism, suggesting that current generations forego consumption to offset anticipated taxes imposed on their descendants. However, empirical evidence challenges Barro-Ricardo equivalence, citing liquidity constraints, myopia, and uncertainty about government budgets that prevent households from fully internalizing future tax burdens, thereby undermining the theory's predictive accuracy in real-world economies.

Policy Implications of Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian equivalence suggests that government debt issuance does not affect overall demand because rational consumers anticipate future taxes and increase savings accordingly. This implies that fiscal stimulus funded by debt may be ineffective in boosting economic activity, as private savings offset public spending. Policymakers must consider that deficit-financed policies might not stimulate growth if households fully internalize government budget constraints.

Ricardian Equivalence vs Keynesian Economics

Ricardian Equivalence posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes to repay debt, leading them to save rather than spend extra income. Keynesian Economics argues that fiscal policy, particularly government deficits, can stimulate aggregate demand and boost economic output during downturns by increasing spending. The key difference lies in Ricardian Equivalence's assumption of rational, forward-looking agents versus Keynesian emphasis on liquidity constraints and imperfect foresight driving consumption behavior.

Limitations of the Barro-Ricardo Equivalence Model

The Barro-Ricardo equivalence model assumes perfect foresight and rational intertemporal optimization by consumers, which rarely holds in real economies due to information asymmetries and behavioral biases. It overlooks liquidity constraints and heterogeneity among agents, limiting its explanatory power for observed fiscal policy effects. Empirical evidence often contradicts the model, highlighting challenges in applying Barro-Ricardo equivalence to practical economic policymaking.

Modern Views on Fiscal Policy and Ricardian Equivalence

Modern views on fiscal policy challenge the strict assumptions of Ricardian equivalence, which suggests that government debt issuance does not affect overall demand because households anticipate future taxes. Barro-Ricardo equivalence refines this concept by incorporating intergenerational altruism and forward-looking behavior, yet empirical evidence shows that credit constraints and myopic preferences limit full equivalence in practice. Current economic research emphasizes the importance of these frictions, leading to a more nuanced understanding of fiscal multipliers and the effectiveness of government spending.

Ricardian equivalence vs Barro-Ricardo equivalence Infographic

difterm.com

difterm.com